I saw a post about a week ago by a Twitter account called Attention Mech. I can’t see the actual post anymore because it appears the account has newly limited the people able to see their output, but it went something along the lines of:

If Elon Musk is a global n of 1 for executive function, who is his equivalent in the world presently for taste?

Attention Mech runs an engaging systems-oriented aesthetics account. My reaction to seeing them pose this question was "Ah, their followship will surely have interesting answers to volunteer to this". So I dove into the thread, which you can still see, decapitated though it is, here.

It turns out that the followship’s main candidates for the title of World’s Most Outstanding Paragon of Taste were:

Hip-hop producers

Phil Knight, the Nike guy

One person suggested, with their honesty-to-God, that the world’s pre-eminent totem of taste must be Hirohiko Araki, the author of manga-anime Jo-Jo's Bizarre Adventure

Some other people said Steve Jobs, and there were a few more interesting replies — an architect named Bjarke Engels; hotel designer Liz Lambert; we saw a few “Leonardo Da Vinci hands down”s — but that was about the best the audience of tech professionals and assorted TPOT types could manage.

Taste, as one of those rare concepts that simultaneously seems not to exist and yet must exist, interests me relative to what I wrote about in the piece “Shogun and the US Election” on the subject of upstream thinking.

In that piece, I justified upstream thinking — the formulation of wild hypotheses charging that event x is, in contravention of everything apparent about event x, actually caused by seemingly unrelated phenomenon y, phenomenon y being so remote from event x that not only would few people suspect the correlation, but that proof of the relationship if it does exist would be ostensibly impossible to obtain anyway due to the amount of noisy distortion and affective interaction played upon and brokered with the dynamic by all the forces intervening between the two elements in the space of causation — with the example assertion that Americans find themselves in a position where they’re offered the choice of terribly unideal candidates for high political office because they make such crappy TV shows.

Or, rather, the reason they find their tree of political choice to be so fruitbare is the same reason they find themselves unable to make good TV.

Here’s an even wider and more wildly general upstreamerous claim. I make the suggestion to you here that a large part of the torpor from which our world presently suffers — particularly in relation to our flatlining ability to build technology that is not dopaminergic and sterile, to produce art that makes us worthy of our time’s immortalisation, or to manage such basic things as the formation of functional relationships and productive family units — is because the answers given above to the question “Who are the world’s most tasteful individuals?” were all so bad.

If you expect this proposition to be proven within the bounds of this humble essay, becalm yourself. It won’t happen. It can’t happen. The proof or otherwise of such a vast assertion is something that requires the parallel, loosely coupled investigation of many people — perhaps dozens; perhaps hundreds of thousands — working in mutually-ignorant unison, propelled by an identical and probably independently conceived suspicion and prejudice to mine, across generations or perhaps a lifetime. If when that time is past, and the situation of our world in relation to those factors enumerated above have improved and the state of our taste with it, then perhaps we will have our proof. Perhaps. It could never be known for sure, however obvious it might seem.

The relevance of my claim that a deficit of taste is, if not the cause of all our issues, then the great symptom of it and the guarantor of those issues’ continued health and predominance, was echoed in something else I saw written in a similar context recently:

“Early 2000’s culture was a desperate gasp against nihilism. “There must be something more!” You see it in movies: Office Space, Fight Club, The Matrix. You see it in music: Evanescence’s Bring Me to Life, Linkin Park’s Numb. Then the iPhone came and the cries fell silent.”

I suppose I ought to find it oddly endearing or at least existentially disturbing that people are starting to try to romanticise or rose-tint (to roseate?) the 00s, that most unlovely and unsentimentalisable of decades. It is true in some senses that some early 2000s culture was a desperate flail against nihilism, and a bid for the idea that there must something more substantive to life that the 20th century’s prolonged spiritual recession had by then made us too poor, in soul or intellect, to afford.

But the most outstanding shared trait about those examples of 2000s culture, which are indeed representative of their decade and of some kind of struggle against nihilism, is that they are awful. “Numb” and “Bring Me To Life” are adenoidally histrionic. They are true expressions of their respective writers’ feelings, for which they deserve some commendation, but they are completely bereft of technical command (bland harmonic development, melodies with non-existent lines of interest, flattened hyper-compressed production and two-settings dynamic range), artistic beauty, or, ultimately, emotional depth. They are dysfunctional at the emotive level in the same way a profoundly depressed person often is; it is not that they fail to evince or experience emotion, but that the emotion they evince is broken. They are the sound of a pathology being rehearsed in a way that is likely to push the person suffering from it deeper into its grip. If the nihilistic anomie of the 2000s was real, neither of these works would help you escape it. To quote a man whose fame proved that elevation of high-tastelessness to international esteem was by no means an invention of the 20th and 21st centuries, and that feats of both great taste and terrible absence of taste can stably occupy the same body, “To write so as to bring home the heart, the heart must have been tried.” But that alone is not enough.

Fight Club stands alone among those totems of putative 2000s anti-nihilism cited, as the only one among them consistently and vigorously praised as a work of worthwhile artistry. It is certainly the most serious (and self-serious) of those works, and the most analysable; and it is useful in this regard, in that it proves neither seriousness of ostensible intent nor analytical readiness have any intrinsic relationship to quality. It is, at best, an unremarkable artistic performance of the Nietzschean habit of trying to give physical violence a sham philosophical basis, and it is an honest depiction of the Millennial anomie — which, in this case, is whatever condition as would prevent someone from grasping the notion that enjoying their pretty nice apartment is objectively preferable to inflicting sterile violence on others — but it says nothing about what it depicts. It is, like most German philosophy, somewhat enjoyable to discuss within the context of its own literary orthodoxy but offers little to anyone minded to pose it against its greatest nemesis, its greatest nemesis being a walk in the park and admiring the sparkle in the eye of a friend one has not seen in a long time and has met unexpectedly.

The exhibits aside, I would challenge that last line of the diagnosis.

…Then the iPhone came and the cries fell silent.

Instead, I would charge, though the arrival of the iPhone inaugurated the economies of dopaminergy and put us all on a path more generally — if not, in absolute terms, necessarily (assimilated-knowledge-of-man-in-your-pocket and all that) — hopeless than the one we were already on, the cries of resistance fell silent because the resistance was so weak. If Amy Lee, the much-too-soon-departed Chester Bennington, and Chuck Palahniuk are your champions against the darkness, you are not going to beat it. As the torturously tangled and ultimately gnomic philosophic shape of Fight Club (intellectualised only as cleanly as a bucket of hairball code) shows, you would barely even have the means to understand the anomie you were fighting against if these works of cultural illumination were all you had to go by, let alone have anything to resist it with. They are works that clarify, delineate, and seek to answer nothing (unsurprisingly in the case of the latter, as these things come from an artistic lineage that sees the attempt to answer anything within art as a kind of formal sacrilege). They imitate what they show, like a crude painting of a tiger on the wall of your cave to which you have returned, cornucopia in hand, to find it strewn with your family’s sundered limbs. Perhaps they validate what they show emotionally, too, like a slur of blood under the reach of wall where the tigershape was scrawled. But they leave you unequipped with the crossbow, fortified hide, log-bound living compound, nemesean psychological fortitude, or knowledge of big cat behavioural traits which you would need in order to move beyond simple knowledge of what ails and has injured you. They are primitive, limited.

This is meaningful, because these works described are the works that the general taste of the period anointed to the heights of popularity. Just as meaningfully, they are such works of the period as contemporary taste sees fit to remember.

There is another somewhat creeping quality shared among those works, which quality is now owed its formal definition as an instrument of aesthetic theory — I refer to what the British have, for many generations, known as naffness.

In the year 2013 it was my privilege to observe, as my own life took its final meander out of youth and into young manhood, the 2010s begin. Yes, decades rarely begin in their zero-year, or indeed even in their first two years, as collective culture’s struggle with numerological determinism stabilises the arrears of the prior period’s cultural exertions and looks forward with balanced books to something new. The third year is usually the one where it starts. In 2013, you could observe all of the following:

Instagram become the most culturally decisive among widely-used social media platforms

Canadian rapper Drake begin his slow climb to a position of relative cultural ubiquity, wherein he would become the first dominant artist of the streaming era

Frozen be released to vast popularity, becoming the first film of note to carry the Disney insignia since the company’s renaissance

British rock band Arctic Monkeys release AM, sporting a greaser-rock look which revived their faltering commercial fortunes; elsewhere Pitchfork declared ILoveMakkonen’s “Tuesday” the song of the year

The leagues of highest-grossing films become consolidated property of superhero movies, family-film franchises, and sequels

If any of these figures are familiar to you, this will seem like a rather regrettable period to look back upon. For the purposes of our discussion of taste, this is the point. 2013 was the period where Naffness transitioned out of being a merely insurgent force of cultural antagonism, as it had been ever since culture was made a mass-communicable industrial force by the Americans, into being culture’s dominant mode. 2013 was the commencement year of the Nafferonic Period.

Allow me to explain what I mean. Naffness is a state of low quality that is ostentatious about itself. Some things are bad entirely innocently of themselves. Some things, however, positively glory in what is bad about them. They insist on themselves irrespective of their right to be insisted upon. Addressed relative to the totems of 2013 just enumerated:

Drake is a singer/songwriter whose artistry comprises many dimensions. He is unskilled in almost all of them — a tonally atrocious singer, an uninspiring rapper; a writer with no subject but himself, which singular focus he harnesses to no artistic use whatsoever. Endlessly verbose and comprehensively without muse. If “Numb” is the rehearsal of a pathology, Drake is not sufficiently developed to have a pathology worth rehearsing (except, perhaps, the unique one shortly to be assessed). His is all the underdeveloped sense of self inherent to the actor, without any of the actorly skill of being able to devise a worthwhile substitute for the lack.

The Arctic Monkeys’ pose as in-earnest 50s grease-rockers struck at a level of conviction and believability that would have failed to impress some of the better Eddie Cochrane enthusiasts (or, for that matter, Elvis impersonators) on the Northern English club circuit, an act as limp as their fundamentally unskilled acquittal of desert metal on the album that their new aesthetic was linked to.

Frozen, a film remembered chiefly for its songs, is a far-cry by any technical or artistic yardstick from the standard of musicianship, theme-craft, and unifying aesthetic you will find in any of Disney’s golden age musical settings. Its well-meaning Mattel-standard feminism amounts to nothing substantive, with the final package being far less organically feminist in the impact it yields than far older Disney films were that treated the theme with a less onerously self-conscious handle.

The Marvel movies of the period, all of them so consistent in their carriage of such traits as are about to be described that picking one of them as representative is unnecessary, are beholden to the most bankrupt creative idiom as has ever prevailed in mass entertainment. A vast array of characters indistinguishable from one another, saying insipid and witless things to each other, engaging in endless poorly choreographed combat sequences whose stakes we are expected to credit as universal in scale but which carry as much dramatic weight as a 72-hour-long lunchtime adventure show at a regional theme park.

The 2010s was a landmark in the recent history of taste because, where naffness previously dominated in those regions of popular consumption where sincere interest in the possibilities of worthwhile art simply failed to predominate, it was in this time elevated to the status of ‘the good’. The critics — those much-maligned critics with their cheap resentments and philosophical alcoholisms, whose responsibility previously was to guard the gates of the ostensibly ‘good’ from the majoritarian tyranny of the naff — defected from their posts and switched their own allegiances to the naff, predominantly as a show of disdain for what in the conventions and demands of taste seemed too historically ‘male’ or ‘white’ for their newly revised and more racially self-critical identitarian ethic. The often reflexive nature of naffness became feted, and unabashedly used, in this period too. If the dialogue in Marvel movies is witless and inconsequential — that is, if it’s bad — then that is because it’s supposed to be bad, stupid. This argument, which would have been too shameful to have been advanced in earnest in any other time previously to defend conduct or creation, became endemic to discourse about these things in the 10s. That it amounts to nothing except a bullish insistence that what is bad is acceptable in and of itself so long as its worthlessness is intended, is rarely subject to subsequent challenge.

And just as characteristic of nafferonic apologetics is the common contention that, if the naff has any even momentary or marginal redemptive quality at all, that is enough to justify its presence. “Yes, it might be bad, but it’s easy to listen to/my kids like it/it’s fun”. Fun. Joy. There has been a pained and concerted effort in the last decade to associate taste with arid Stentorian discipline and cultural elitism while naffness is associated with naturalism and equality and ‘joy’, the natural endgame of which is nothing less than the Kamala Harris campaign, whose genially unaffected insanity was evinced not only by its insistence, naff-suprème, that only a spoilsport would deny the most unqualified people imaginable their chance at running the show in America, but that the ‘joy’ they insisted was at the heart of not just their campaign but their philosophy looked, to the impartial observer, as convincing as an array of marzepan artillery shells and as corrosive as a barbiturate overdose.

Naffness is material to our discussion because it is not just the absence of taste but the dereliction of it, and active resistance to it — it is a statement rooted in a kind of ressentiment that what is good is to be actively run over, resisted, and despised as the work of people whose capabilities outstrip conventional norms. Instagram’s position in this is not unimportant. Instagram is not merely a pastime, but a transformative way of viewing the world. Because it has no standard or principle set but devotion to artifice, and because it is dopaminergically addictive, it becomes those young people who use it, young people who:

Cease to be able to differentiate between the artificial version of themselves that they purport through the platform; and their ‘real self’

Cease to be able to differentiate between the artificial versions of others they see on the platform; and those people’s ‘real selves’

Cease to have time, dispositional inclination, or intellectual resource — that is, interest in the real world enough — to assemble any kind of ‘real self’ as would make such discriminations possible or necessary anyway, because Instagram is where time is to be spent and tropes of reality are not a currency as can be spent on Instagram

It is not a coincidence, I think, that as Instagram began to dominate, the voices of culture most elevated by mass approval start to belong to people who are themselves simultaneously completely affected personalities, and profoundly unconvincing in the personalities they affect. Kids in 2013 and beyond didn’t know who they were and could perceive within themselves their intellectual and spiritual under-development; they wanted to see people on their screens and hear people in their ears who perceptibly didn’t know who they were either, and who had as little to say as their audience did. Those chained to mirrors starved, and having been mangy philosophical orphans whose inheritance was the Saw movies and reality television anyway, they had no means to even parse the naff from the tasteful. And no wonder. Instagram, being something that insists on itself with no justification for doing so, is naff. The people it produces according to its dictates are themselves naff: self-assertive, dismissive and proprietary, not necessarily unintelligent but full of unknowing, with little to offer. As people of such composition will do if they are not entirely redeemed by ignorance and stupidity, they despaired, and despair still.

There is a kind of decadence in naffness. It is not like the struggling beginner, or the contented amateur, the latter of whom knows their work may be limited but takes too much joy in the modest and triumphant act of creating it to care (which is exactly as they should feel about it). It is acceptance, tacit or conscious, of the limited quality of your voice and the determination that it should be heard loudest above all others anyway. The guy in “Bring Me To Life” must know how ridiculous he sounds when he cries ‘Save me!’ in the song’s chorus as a responsory to the main vocal line. Hearing it out loud evidently did not chasten him into phrasing the line differently, or dispensing with it altogether for something more elegant or beautifully assembled. The systematic denial of that instinct to be embarrassed of what is bad is the dominant, or at least the definitive, strain in our culture now.

So that creeping naffness of 00s culture became patent in the 10s. What of the 20s, where we live now? In short, it can be summed up by a sectarian death chant sung at a music festival for the moralitarian upper-middle class by people dressed like this — tastelessness but of a more violent and radicalised hue to the glumly hair-clayed, Hollisterian whimsy of the 10s. What was not inherited by the lights of the 00s and 10s was not spontaneously re-inherited by those of the 20s; they have built upon the ignorance, the technical ineptitude, and the utter alienation from history from which their predecessors suffered (and by which they guaranteed all our suffering) and, by dint of what their cognitive and epistemic vulnerabilities (which vulnerabilities are themselves, as they were for the Platonists, the ultimate harbingers of a fall from taste and thus from civilisation) have allowed, they have created something even more complete. It is an era now of those who retain knowledge weakly because knowing is of no object in their world where time and space as apportioned by attention are but limited matter. It is an era of those who inherited no intellectual frameworks or birthrights of principle because their forebears possessed none to hand them down; an era of those who are as starved of technique as they are of knowledge, and who are locked into patterns of behaviour which deprive them too of genuine experience in favour of the nested mediations of purely online-life. As those so comprehensively disinherited from glory will, they despair, even though they do not really know what they have been dispossessed of, nor the extent of their dispossession. Hatchlings, in a nest high on a formidable outcrop, hungry and motherless. As is only their nature, they cheep loud and mournfully day and night for that which is not alive to return to them.

In such a desolate context, ‘taste’ seems as pointless a concept to investigate as ‘GDP’ would be a measure of the activity occurring on a still-gestating planet with a liquefied sun-hot surface. The sociocultural phenomenon to bear most in mind here is the complete loss of lineage. If you, like any other person of taste, have ever found yourself reckoning with the fascinations of cephalopodic life, you probably spend a moment or two per week refreshing your gratitude that the concept of neoteny — that is, child-rearing and parent-child relationships — doesn’t exist among the world’s octopus population. Why? It’s likely otherwise that if octopi — with their fierce ability to accumulate learning, their morphological capabilities, their adaptability, their superior limb-count — could pass on their knowledge from one generation to the next, they’d be rulers of the world, or perhaps be contesting us for the accolade. But octopi have no history. Neither, and more with each passing generation, do we.

Perhaps the octopi despair, though I expect not. What they do is in no violation of their nature. What we do to ourselves is in direct violation of ours.

What is the product of this condition of things, where knowledge and skill are mutually alienated from the wider mass of people, in terms cultural and supercultural? Well, it doesn’t merely have ramifications for the standard of music we listen to or movies we choose to watch. In an era that has transitioned from seeking meaning in nihilism (the 00s), to seeking meaning in trivia and trifles (the 10s), to now seeking meaning in shallow awfulness (the 20s), it seems deeply appropriate that the only dynamism, the only energy of industry in a place like Britain, for instance, is devoted to what the Economist recently described as "scuzz, smut and sin": sports betting, entrepreneurial pornography, and criminal activity are our primary growth vectors and, unlike countries like China, we include these strains of activity in our GDP figures.

This is the product of your taste — not idle entertainments, but the conditions of your existence. The very same instincts that lead you to waste your life in the consumption of trifles will spur you on to misspend the rest of your time, too and, eventually, they will spur you (or at least ‘you’) to violence (how’s that for upstreamery?). If you are sensitised only to the ugly, and cannot be appealed to by the high, then the ugly shall be your milieu, and just as there is no hard limit (in light or heat or subtlety) of the beauty we are capable of apprising given the sense to do so, there is no hard limit on the depths of ugliness we are willing to entertain shorn of the defence of our taste. All such things as we have inventoried are mere failures of discernment; the failure of the same limited set of synapses to fire as they ought to. I said earlier that the correlation between our failure of taste and our exile to this derelict station was unprovable, but maybe it is only unprovable insofar as the correlation between oxygen and the setting of fire was in the times before Priestly and Lavoisier.

But, I digress too much. Let us return to that most visible and acute signal of such conditions as are ours: that, when asked to name their paragons of taste, now even relatively intelligent people will have only the means and awareness to give, as they did when Attention Mech asked them, names like Rick Rubin and Kanye West and Hirohiko Araki. That people would even seriously venture such answers to such an important question tells you about the paucity of our inheritance, when in times gone by and contexts-removed they could have said Panini or Federico da Montefeltro or the architects of Samarkand or Germaine de Stael or Wang Xizhi or at least Coco Chanel or someone like that. Still, let us not simply marvel at our poverty. Let us break down their answers and see what they really tell us about our situation, where taste is concerned.

First and foremost, designating hip-hop producers as paragons of taste is insensible, the recorded output of the two individuals named left aside — which outputs amount anyway in their cultural weight to a fresh pair of Reeboks and a designer handbag with nothing in it, respectively. This is because hip-hop, as a genre, was conceived against taste. It is, in general form if not necessarily in toto, naff. Its precondition was that a group of people who could not sing were determined they ought to be the focus of attention at the party anyway; and that they, alongside their compadres who couldn’t compose instrumentals but could ‘produce’ their way to music by taking samples of stuff more able people had made previously, had as much right to assert themselves in a musical arena as anyone else. Notions of the genre’s ‘poetic’ superiorities — poetry in pop music post-hip-hop has sat, if anywhere, at a slightly lower waterline than the relatively unremarkable level it sat on pre-hip-hop — were then derived as themeing to justify the naff premise of the deal which is that the guy who can’t sing demands that he’s going to sing anyway. I enjoy hip-hop less than I used to, but I occasionally still dig it, in the same way that I still enjoy some post-modern artworks as articles of discrete interest and entertainment value, though they cannot work for me on the same level as a Rembrandt or a Repin. But it is pointless to conceive of hip-hop in relation to taste. It was born in explicit opposition to notions of taste. In its mythology, taste is for lames, people not cool enough to get it. Its standards of technical command, artistic beauty, and intellectual depth are, at best, its own.

The same goes for manga and anime. It is, like hip-hop — with which it shares an unsurprising affinity — a mode conceived in antithesis to conventions of taste, to allow expression to those whom conventions of taste would otherwise exclude from the arena. Though hardly bereft of artistic worth, it is a mode run by artists who cannot quite achieve the pedigree of the finest arts. Its command of the human scale is generally equivalent to the two Western forms which have most inspired it, sci-fi and fantasy literature; that is, like them, manga tends to be moved by cardboard cut-out morality, implacable villains, a conception of the world that teenage boys can find themselves comfortable with, and an infinite and ultimately numbing extension of basic conceits not fit to feed a chivalric romance for volume after volume after volume. It is art designed not, in general, with a view to engagement with or confrontation of conditions of real living, but, again like western fantasy and sci-fi, to exclude as many worldly things as possible, in the name of a kind of systematic worldbuilding that was also the engine of the German rationalists’ great opi (though unfit for their standards of aestheticism, it must be said).

Manga’s command of the universal scale, where monsters frequently grow to the size of galaxies, embraces the ridiculous and generally contrives to defeat any sense of that proportion which is so inextricable from harnessing of the dramatic. Its sense of the dramatic itself is sentimental, histrionic, sensational — everything from its pornography to its sense of kinaesthetic poise and posture (the latter given especially characteristic depiction in Jo-Jo itself and its famous poses) reaches unabashedly for the preposterous, and is practised past the pale beyond which notions of beauty and ugliness subside, Liebesnacht-style, into each other. It, by-and-large, knows little about human nature, evidenced in the thinness of the science of interaction that generally governs between its characters. If you wander — as I did — into a Naha City department store and see the shelves of one aisle after another stacked with manga dedicated to abominable demon hordes, flatpack heroics all threshed with stark violence, in worlds devoid of any scale of normality, and decorated with female characters acquitted so that they as nearly as possible resemble absurdly buxom nine-year-olds, you have a roughly representative picture of the mode.

Naturally, and like hip-hop, because the form is so widely practiced and gives vocation to some clever people, there are exceptions to these common limitations. Some manga is alarmingly subtle, delicate, and moving; in these respects it can often be found carefully emulating fields beyond it which are more amenable in their norms and customs to artistic achievement of a high calibre. Its relative resting height can be adjudged higher or lower, but a piece like Kotaro Lives Alone hardly disgraces its position in the lineage of Lindgren, Pearce, Milne, Kipling, and Vessas in his Ice Palace, among works essaying that most difficult of subjects — the psychology of children. It is cute but not cutesy, modest without being reductive, restrained in its traumas without being anodyne or patronising. It is as accessible and gentle as it is powerful, a positive antithesis of the naff.

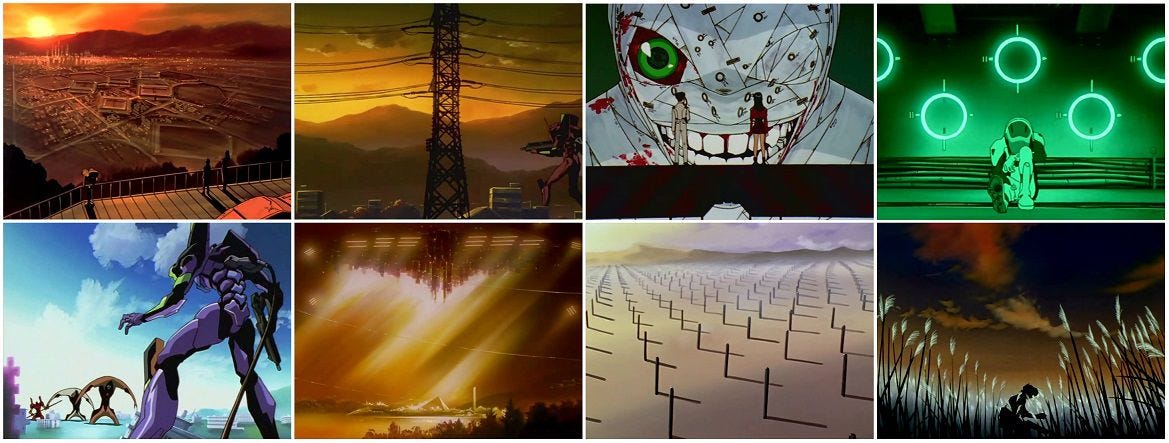

There are those works, like the original Neon Genesis Evangelion, which are of unprecedented quality — indeed, it’s a masterpiece by any measurement, wrought with dazzlingly acute symbolic imagination, beautifully engineered in its narrative, and gifted with such command of the psychological spectrum as would do little dishonour to Balzac and Cao Xueqin. Moreover, not only does it boast such mastery of intimate settings, but when it takes on sublime topics they feel full of aggravated terror and awe-inspiring dramatic scale, secured by a thorough thematic unity. It is a haunting and ravaging piece of work. It has kept me as its captive since I first saw it as a youngster. And just look at the shape of its triad. Artistic beauty, harrowing as it is; technical command in abundance and in defiance of budgetary constraint; and such emotional depth that few emerge from it untutored in some dimension of themselves they probably did not much wish to understand more deeply.

But for occasional lapses of taste and courtings of cliche in its detailing and in the genre tropes it resists with progressively greater conviction as it goes on, naff, it is not.

It’s not of quite the same calibre, but an even more pointed version of the same captive effect was exerted on me by an anime named Gilgamesh; I will write about it here purely because there is almost no writing about it anywhere else, and I wish to give my vagrant affection for it some measure of imaginary friendship. It aired once-through in Britain in about 2007 on an obscure music channel called RockworldTV. I saw only a single episode of it then, one with no notable incident or event in it; and it only occurred to me very recently that in spite of this it ended up worming its way under my skin and becoming an archetype in my personal imaginative toolkit. Its nomenclatures, its tone, its setting, the Sumerian tropes with which it garlands itself half-committedly, its in-world fashions, its swirling darknesses so deep they shine; I have found myself using them in the years since as benchmarks and imaginative shorthands for things without meaning to and in some cases without realising it. And when I returned to it recently, I found that the part of me that I engaged to watch it, now as then, had not aged a day. I began watching it again as though no time at all had passed. I am tempted to say that this way in which certain objets d’art keep a part of the audience immortally preserved, beautifully starved and fluffed for immediate re-summons, in this way is merely a function of nostalgia, but I notice that many other works of my younger fascination, including those with which I had a much longer and deeper relationship, no longer have anything like so pronounced an effect on me.

While the show makes opportunistic metaphor of the epic of Gilgamesh and the great old Urukian’s search for immortality, it is not much of a re-telling of the tale. It’s about two groups of teenagers with psychic powers battling over the fate of a fallen world. Two ostensible orphans — fathered by the man who made this version of Earth, with its mirrored sky, what it is — are caught in the middle. It is a generically unpromising premise. Most obviously remarkable among its constituent elements is its art style. The characters have a sloping elegance about their lines. They are sparsely animated, as though left in poverty-of-lifeforce by their circumstances, or as if the show was originally conceived of as a play for marionettes. Their lips are generous and masticatory, their hair delightfully luxuriant. Their eyes are unbearably penetrating at all times — the only animated eyes I have ever seen which look out of the screen just as Rembrandt’s Jan Cornelius Sylvius’ hand gestures out of the frame; the only animated eyes that see — which quality one takes as mere organic product of their world, one without sunshine and, as so described, dark as crows sipping coffee from an iron kettle while sitting at the bottom of a mine shaft in the middle of a moonless winter night. These are eyes made for squinting against such umbras. And eyes fit to look with such sensuous force are appropriate; the darkness of the work is ubiquitous, but it is a markedly vivid one, worth looking at.

My wife despises the intensity of my reverence for Francisco Goya, because she considers him some variety of black magician. She believes that I can look at his works for a few moments and then be submerged in a depression it takes me all day to come out of. I often find myself moved by Goya’s work, indeed perhaps no painter can move me in such a variety of directions with such weight and force, but the intense currents of unbeatable humanism that roar beneath even his most desolating work — it is this that distinguishes him as an artist of the highest calibre, and this that all those who have the grain of taste within them will respond strongest to when looking at his oeuvre — that I find even El Perro or The Burial of the Sardine not comforting, per se, but comfortable, as if they provide some kind of waystation for my soul, in their terrible way.

Nevertheless, it must be said that the effect my lady erroneously describes Goya as having on me really is exerted upon me by Gilgamesh. There is a prolonged broken scene in the later part of the show in which a character begins secreting a vile accretive ooze which evenly becomes a cocoon around them, within which they slowly decompose while their loved ones look helplessly on. I can only describe this as a perfect shorthand for the experience of watching the show. It can be violent and it is, in many senses less than obvious, richly disturbing; but there are far more openly violent and effortfully disturbing things out there that I have seen and can barely now recall. No, it’s that, through some uncanny alliance of elements, the creators of the work have composed and sustained a hopelessness of great subtlety and unparalleled weight, a vision of despair t hat is utterly seductive. As things get progressively more bleak and horrible, there do I sit like some sort of Incandenzan, unable to restrain myself from loading up the next episode, convincing myself to push through the pressure of the succubus fattening itself on the throne of my chest as though doing so were some kind of show of strength. Before its end I am convinced it is an evil show that wants me to die a death of despair. Given only the elements this work affords itself — refusing as it does to rely on such tropes of extreme violence or cruelty or degradation as craven authors otherwise will use to make their audience feel unclean, and which could even still not produce such an effect as I describe — nothing but something that is quite exceptional could create such a feeling in its viewer.

Made in 2003, it would be tempting to suggest it too is an emblematic work, perhaps some kind of masterwork, of 2000s nihilism. It certainly gives neither lie nor panacea to what it depicts, which is what I charged the work of Linkin Park and Evanescence with failing to do. And yet, its artistic qualities are extraordinary, in some cases to be admired in spite of some clear conventional deficits of basic presentation, though I don’t mind them myself. And yet further, I cannot entirely convince myself that it really is nihilistic, though almost everything about it begs me to do so. Perhaps this is because a level of quality such that smothers and adores the grain of taste cannot be the product of an entirely nihilistic or cynical imagination, which at least holds enough light of belief within itself to think great work worth the effort to achieve. It is flawed, perhaps dangerous; but, again, and, with the helpful contextual exception of its opening theme song, not naff.

Of what little I have read as was written about this obscure work of early century rococemo television, the theme persists — you couldn’t make something like this nowadays. Those who have never heard a word breathed of the show, and who would derive nothing from it if they watched it, know this nonetheless to be true, and mourn it. Peoples who cannot produce anything worthwhile will see the world as a bankrupt and hostile place — I myself need look no further for proof of this than to my hands as I write this essay, for each time I find myself up against an obstacle in thought or expression I find myself confronting that same feeling in miniature, a feeling dispersed when I have overcome the challenge in front of me.

But I do not generally despair when the challenge arises, just as I don’t when taking this sorry picture in summum. Why? Because the straits we have described, while engulfing and well-fortified at their base and showing no signs of abating as yet, are far more vulnerable than they seem. Nothing built on sloth, ignorance, or incapacity is very strong. History offers us the rhythms by which stages of distinctly undistinguished civilisation, or else periods of outright abeyance in civilisation altogether, unceremoniously and suddenly evolve into periods of cultural flourishing and high attainment.

Taste is, in its way, a kind of Virgilian figure, a Jiminy Cricket — it is the harbinger, the forebear, the guide, the aura, the pre-evening predictor and symptom of civilisation. Where it is strongest, civilisation flourishes most. Where it is weakest, little of worth or note will be achieved. How, then, to allow for the conditions required for it to flourish?

Fertile knowledge traditions, serious and well-guarded by a base of criticism, seem to be one pre-requisite. If you cannot inherit knowledge from those who have delicately preserved what prior generations have discovered, you will develop neither the reverence for history nor the fingertip-familiarity with the limitations of your pursuit that taste allows. If you do not have people who are able to analogically explain the virtues of a form, you will find too that it does not survive long. Critics are often derided but Beethoven owed something great to ETA Hoffmann, just as Bach owed something great in his afterlife to Mendelssohn — they are those who transmit the context critical, if we are honest, to our understanding much of the good. Some of what is great is entirely accessible to us even if we aren’t literate in its idiom. Much of what else is great is not.

Undergirding that knowledge tradition must be a value system, and not merely an aesthetic one. In our time, magnanimity is considered the ultimate virtue — our era in which judges do not judge, except for when they judge those who would judge — and so it is that we have forgotten what a critical, if unprepossessing, role chauvinism has in defending the boundaries of our discernment. We must be willing to assert our standards as ours, and as in some senses superior to the alternatives, to whomever they may belong. This is necessarily concomittant with preparing to be wrong, because to have a value set — whether about the way in which children are raised, our attitude towards agents of law, our toleration of others foibles including intolerance — is to eventually be put in a place where the value set fails you, or you fail it. Many people today live in deathly fear about this, but if I weren’t able to assert what I consider the fact of my own values and the way they shape my powers of discernment, I would be stranded in our conventional context, where I am obliged to think of all works of human imagination and effort as equal. Given they so manifestly are not, however we set about benchmarking them, this will result in cognitive dissonance, as results whenever we ignore what is manifest, and a life surrounded by pabulum, suffered for no reason other than that we wish others to think well of us.

The valuation of technical capability in a pursuit also appears to be essential, but prior even to that, knowledge of all the different forms of technical excellence in a given form must be established. In music, for instance, there are forms of technical excellence that are almost purely mechanical, but they are extremely different from those that relate to the capacity to create melodies with extraordinary interest lines, or to build harmonic schemes with beguiling emotional power. The forms of excellence are so different, in fact, that mutually exclusive practitioners of the one can seem alien to those of the other. This sea-ration, however, was clearly not the norm in the past; within the bifurcation, a 20the century phenomenon, there may be further clues to our present predicament.

I could go on with my inventory. In time I shall. These things numbered are themselves gateways far more than the simple ability to tell the bad apart from the good — in their great hulking contexts, taste seems modest. But then that is exactly what taste is. It denotes little by itself; it is merely the sign that you are in a place where the truly good, the truly valuable, the truly beautiful, can be made possible. It is the kodama in the forest of human meaning. When in its domain, we do not focus much on it, except that we occasionally hear the rattle of its lovely little head tilting in the wind, or the reach of its yamabiko, echoing delayed into the mountains and valleys of the commons around us. But for those moments where we glimpse it, and are seized by gratitude for its thankless place among the human faculties, we are too busy enjoying the lushness of the woods of creation with which the kodama lives in a holy mutual guarantee.

And that is how it was meant to be.

Things to Spend Your Taste On Wisely

As much as it is intended for anything else — like, for instance, to salve your spirits after such a bleak essay — this addendum is primarily here so that we may end the day by losing ourselves in an orgy of fantastic work built with the most acute of taste.

But wait, what’s that?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Heir to the Thought to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.